by Paula Halpin

In 1980, on an icy February day, I waddled into the Pape/Danforth public library in Toronto’s Greektown dressed in layers of clothes that added even more bulk to my pregnant belly. I was there for advice on what I should be reading to help me better understand my new country. I had moved from Ireland to Canada a year earlier with my husband and two young sons, yet I still felt like a stranger in a strange land.

I had somehow expected Canada to be a clone of America, only with more snow and forests and polar bears. US culture was so globally pervasive that unless you had watched National Film Board documentaries in the 1970s (which we occasionally did in my home) you would have had a hard time differentiating between the two neighbouring countries. I picked the right one by chance.

I was desperately lonely my first year in Canada. I moved through the streets feeling as if I had landed in a sci-fi novel where the plot made no sense. At the same time, I understood that, unlike many immigrants, I was privileged to have white skin and English as my mother tongue.

I also remember moments of excitement at finding myself living in a vibrant New World city. By contrast, Dublin was a thousand years old and showing its age. Almost everyone was Catholic and ate the same meat and two veg for dinner each night.

Still, I missed my rain-soaked, good-humoured, talky hometown—birthplace of Nobel Laureates Beckett, Shaw and Yeats. The knot of homesickness lodged somewhere deep in my chest. I kept thinking of that bittersweet going-away shindig that my husband and I had hosted for all the people we loved. After everyone left, I sat in my kitchen, surrounded by used paper plates and plastic glasses and bon voyage cards, drinking a gin nightcap with my teary-eyed father. He asked if I was sure I was doing the right thing. “I’ll be back in two years,” I assured him.

I have been gone now for 47 years, except for sporadic vacations in Ireland.

When I agreed to the move, my husband had promised that if I was unhappy in Toronto, we would come home. Many of our friends were economic migrants in the 1980s. Young families upped stakes and came to countries like Canada and Australia seeking better paying jobs and greater opportunities for their kids. They planned to stay. We, on the other hand, were only looking for a temporary change of scene, a foreign adventure—or so I thought.

From the get-go, my husband loved Toronto. He was soon busy renovating an old

house, starting a business with a fellow Dubliner, and meeting people from all over the world. Heady stuff.

I was home alone for long hours taking care of our boys. When I became pregnant

again, I knew I would not be going back to Ireland any time soon. I could not take three kids away from the good living their father was making in Canada. I needed to start thinking of myself as a permanent resident.

And so I found myself in the Pape library on that frigid morning, my cheeks raw, my eyes watering. I hadn’t yet learned how to celebrate winter. Stop your whining, the hardy natives seemed to be saying. Get out there in your thermal underwear and embrace the inhuman cold. You’ll love it!

The librarian was eager to recommend books about Canada. My knowledge of the country was sketchy at best. There was hockey and Tim Hortons and Canadian Tire and the Mounties and Honest Eds and a flamboyant prime minister who once impishly pirouetted behind the Queen.

Start with the fiction, said the librarian. Best advice ever.

I began with Two Solitudes by Hugh MacLennan and The Stone Angel by Margaret Laurence. The first is a family saga that tells the larger story of the historical divide between colonial powers, England and France. The second is set in Manitoba’s prairie landscape and traces the difficult life of 90-year-old Hagar Shipley.

I then discovered Alice Munro, Canada’s own Nobel Laureate, who told the

extraordinary stories of ordinary people in small-town Ontario. And then there was Alistair MacLeod’s The Boat, a marvellous short story set in a fishing community in Cape Breton.

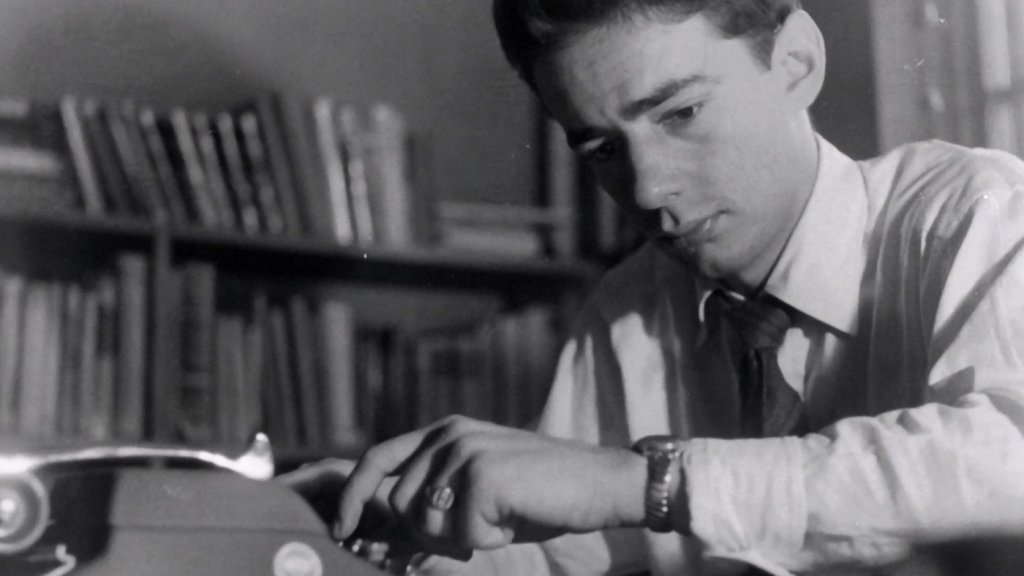

I once curled up on the couch after root canal surgery and laughed aloud at Mordecai Richler’s The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, a brilliant satire about a young Jewish scallywag on the rise and searching for land to call his own in mid-20th century Montreal.

These Canadians can write, I remember thinking.

My ever-helpful librarian set aside other books for me. An anthology of essays by

Indigenous writers had me paying closer attention to the under-told story of Canada’s colonial past and how my Irish ancestors were part of that dark history.

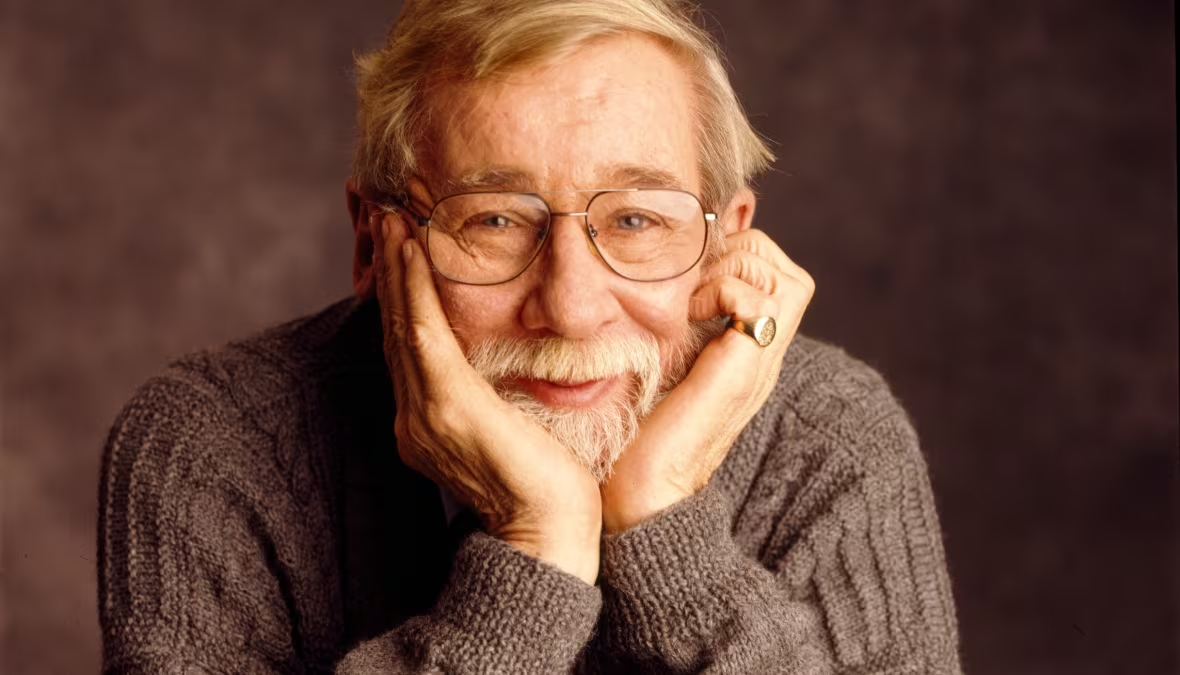

A neighbour turned me on to CBC Radio’s celebrated Morningside program. Each

weekday morning, host Peter Gzowski would speak as if only to me in his gravelly

smoker’s voice while I washed the breakfast dishes. He reported from all corners of Canada, conducting interviews so intimate you sometimes felt you were eavesdropping. It was like having a friend for coffee in my kitchen every morning.

And so, I came to know and appreciate my adopted country.

Recently, when a vain, vengeful authoritarian imposed harsh and unjustified economic sanctions on Canada and threatened to annex us as the 51 st US state, I instantly understood the depth of my attachment to this place – what it means to me and millions like me. It means peace, and compassion, and the embrace of differences, and peerless natural beauty, and, of course, exemplary good manners.

I’m not a flag-waving patriot arrogantly declaring Canada to be the best of all countries on Earth. There is no such place. Perhaps it was former Member of Parliament Jack Layton who, without hyperbole, described this country best. In a farewell letter to Canadians just before he died, he wrote simply that “Canada is a great country, one of the hopes of the world.”

No need for me to go back home. I am home.

Wandering Wakefield readers and writers are invited to submit their essays, stories and opinions about our country to POSTCARDS from CANADA | Alice Goldbloom

| Substack